Published 1911

Approx. 105,000 words

(First read 19/09/2013)

Juggernaut¹ tells the story of Margery Morrison's marriage to Arnold Leveson, of her cousin Walter's thwarted love for her, and ... well, that's about it, really.

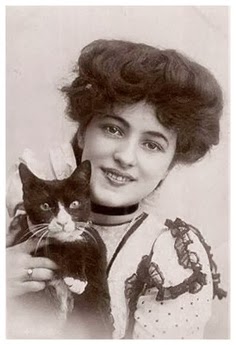

When we first meet Margery she is sixteen-going-on-seven, bawling her eyes out over a kitten which has supposedly been drowned at the orders of her wicked aunt (Mrs Agnes Morrison, widow). Marge is an orphan who has lived with said aunt and her cousins (Olive and Walter) for the past few years. The latter is two years Marge's senior and Benson Type No. 1; the pair have grown up as thick as two short planks ~ oops, sorry, I mean 'as thick as thieves'. But lo! over the course of a walk, during which it turns out the kitten hasn't been drowned after all (phew! that's a relief), Walter suddenly grows up and realizes he's in love with his couz.

Our heroine, as I've subtly hinted already, is a simple lass: to give her her due, she's the first to admit, on more than one occasion, that she's 'not very clever' ~ a bit of an understatement. However, she makes up for her lack of brains by being sweet, flawlessly pretty, remorselessly optimistic, open-hearted, generous, pure in spirit and outlook, kind to animals, loving, virginal, saintly ... yes, she's Benson Young Female Type 1: so entirely good that you find it impossible to believe in her. EFB does his best to convince us she's a bit of a tomboy (or maybe he uses the term 'romp'), but with little success: he's so obsessed with slathering on the 'tiny hands and feet', 'masses of silky hair', 'porcelain complexion' etc. etc. that you're left with the girliest tomboy that ever was.

Into this cozy mix is thrown (very gently) Mr Arnold Leveson, an elderly bachelor (he's about 30 ~ joke!) and all-round dry-old-stick. His great passion in life is writing incredibly long and tedious books about Ancient Greece ~ we're treated to a few quotes: they gave me the dry-heaves, I can tell you. Margery raves about them and, now that Walter has been safely packed off to Germany (!), very soon ends up raving about Arnold himself. They get married. Marge is obviously ~ yes, obviously ~ so lacking in any kind of insight that when, on his return, Walter tells her he's over her and he's fine with her marrying Leveson, she believes him. Walter proceeds to hang stoically around for the rest of the novel, confounded self-sacrificing idiot that he is.

Unfortunately, the marriage doesn't turn out well, to put it mildly². It becomes clear that Arnold loves his Ancient Greek περίττωμα³ more than his wife. Margery joins Walter in the Suffering-in-Silence corner. The End.

No, I don't think I've forgotten anything ... other than: Margery's aunt. Mrs Morrison is the closest Juggernaut gets to comedy: she's another of EFB's 'classic' middle-aged ~ but prematurely-agèd ~ embittered cows, a close relative of (e.g.) Mrs Hancock over at Arundel [qv]. The difference between the two is that Mrs M is actually pretty rubbish at her selfish manipulatings, constantly putting her foot in it, giving herself away, etc. But she's nasty to everybody ~ her niece, her own kids, her neighbours, no-one escapes. Sadly there isn't enough of her, though, to rescue Juggernaut from being a pretty tedious read: the plot is wafer-thin; Margery you just feel like punching; Walter is a moron; Arnold, though 'bad', is as dull and irritating as everyone else; only Walter's sister Olive shows occasional flashes of what might be called 'character', but she's a pretty minor character all told.

¹ Published in the USA under the title Margery, which is far more sensible. The UK title suggests a great deal of movement and noise: the novel has neither.

² Without giving too much away (!), I'll just tell you there's another heart-stoppingly callous Bensonian infanticide involved ...

³ The English is one syllable long and rhymes with grit. Don't blame me if I've got this Greek word wrong: Greek isn't my thang ... obviously.

THE CRITICS

~The Spectator, 04/11/1911

"Juggernaut" in this book is performed by the man, who marries the very attractive heroine, and then allows his literary work so completely to absorb him that her married life becomes a complete failure. Even his wife's health is sacrificed by Arnold Leveson to his book; it is hard to believe that a sane human being could possibly be so absolutely egotistical. The book is written with Mr. Benson's usual powers of observation and analysis, but the nature of the theme is a constant source of irritation. It is impossible to avoid a wish that the scholarly Arnold should meet with some sudden disaster, as that would be the only possible way in which his unfortunate wife, Margery, could be restored to happiness. He declines to allow anyone to come to the house, for fear of disturbing his hours of work, and poor Margery is obliged even to drop her piano playing, in which she might have found an absorbing hobby. The minor characters are well drawn, and the portrait of Margerv's aunt, Mrs. Morrison, is so carefully studied that she is quite entitled to a place as one of the four principals of the book. But here, again, is a study of a purely self-centred egotistical person, and two characters of this sort in one book overweight it with non-conductors of sympathy.

~Frederic Taber Cooper in The Bookman (US), 11/1911The central issue in Margery, by E. F. Benson, is whether a young woman, replete with the joy of living, can find happiness in marriage with a man who has never in his life known a passion warmer than his delight in Grecian urns and Tanagra figurines. Margery is the child of an ill-assorted marriage; and when, as a forlorn little orphan, she first comes to live with her father's relatives, her aunt Aggie takes good care not to let her forget that her mother was a mere vaudeville dancer. Margery is not malicious or vengeful, but just a sweet, wholesome, not over brilliant girl, whose innate goodness men unconsciously recognise. That was the explanation of the failure of all her Aunt Aggie's too obvious manoeuvres to keep Margery in the background, and marry off her own daughter, Olive. Almost simultaneously Margery has the task of refusing an offer from Cousin Walter, Aunt Aggie's only son, and from Arnold Leveson, whom Aunt Aggie already felt sure of as a son-in-law. Arnold Leveson had all his life been a student and a recluse. He had already written one epoch-making volume on the Alexandrine Age, and was now engaged on a companion work, the Age of Pericles. The wonder was that, in his absorption in antiquities, he ever raised his eyes high enough from books to rest them on Margery's face. But such happened to be the case, and presently they were married. And then, for a while, the experiment succeeded. But after the honeymoon and a brief season of London gaiety, Arnold felt a return of the old fever of study, the old impelling need of creative work. From that moment, Margery's loneliness began; and the rivalry was harder than that of another woman, because against a woman she could have offset her own charms, but she was powerless against ancient tomes and crumbling marble. Mr. Benson did not lack a big issue, but of his own accord he dodged it. What Margery and Arnold would in the end have made of their lives, he refused to tell us, because one fine day in Athens, antiquarian zeal led the man a step too high upon a tottering ruin, and when he and the ruin fell together, he was undermost. It is vexatious when a novelist has all the elements that go to make up a human problem of vital interest, and then deliberately shirks his task.

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment